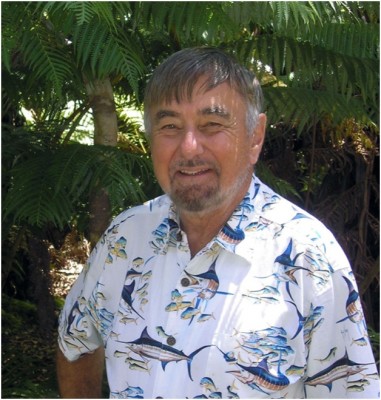

Laurie, Kathy, Dana, and David Van Deusen, looking over the site of their childhood home near what is now the museum overlook. May 2012 photo by John Gorentz.

Where public and private intertwine

It is common for a family to relocate for employment, but to grow up on the premises of dad’s work is not, unless dad is a farmer. At the Kellogg Bird Sanctuary, director Roswell Van Deusen’s children not only grew up there, but their lives were imbedded in the landscape of the daily atmosphere. The work of the sanctuary felt more like a family adventure. Perched lakeside in the middle of the grounds sat the resident director’s home. It later became the Sanctuary museum and the director’s home was moved to a more private location. When the Van Deusen Family arrived five of their six children were born: Joan, the oldest, was in seventh grade; Dana was in the third grade; Kathy in the first; Laurie was four years old and Dave was newborn. Brian, their youngest child, would not arrive for two more years.

A fence provided the only border for the family during open public hours. With no central air conditioning and windows open in the summer, public and private space blended at the whim of a breeze. Conversations were heard of passers by and these guests also heard the noises of interior home activities. Joan the oldest recalls the experience as “living in a public fishbowl.” She remembers, “The privacy fence around the house did not always stop visitors from looking for restrooms.”

Laurie remembers climbing out onto the roof and dropping pebbles she’d collected to surprise sanctuary visitors. Kathy’s memory offered a happenstance encounter. Practicing her oboe one afternoon a gentleman and fellow oboe player knocked on the door to introduce himself. He shared his knowledge of how the instrument was best cleaned by using a turkey feather.

The Van Duesen family grew up with the community as a constant fixture in their backyard, though they all agree that living there was a sort of paradise. David recalls the paved walkways as magnificent bike paths for after hours bicycling and the tall spruce trees were perfect for climbing. He used each branch like a ladder rung and on breezy days he sat at the top to enjoy the gentle sway back and forth. He once abused his access to the bird seed stock and dumped it in the hallway for his trucks to doze around.

Kathy and Laurie sparked their entrepreneurial spirit at the sanctuary. At the gate entrance that separated their private home from the public sanctuary they set up a sales table. Not unlike other young people who sought to sell lemonade, however their goods were the beautiful peacock feathers shed by the resident birds. Kathy and Laurie knew right where to find them and raced to the nests each day to find what treasures the birds had discarded. Displayed in vases, the girls sold them to the visitors who equally valued their beauty. David employed the feathers a different way. He discovered that two feed boxes put together with a feather protruding from its top made a fine boat for sailing on the lake.

There were Pets, and then there were Pets!

When the Van Deusens arrived they had a young rambunctious dog who chased the geese. Who could blame him? They found him a good home, but that did not stop the Van Deusens from having pets. They had many dogs either retrievers or German shepherds over the years and even a Cat. A cat at a bird sanctuary doesn’t seem plausible or like a good fit. “Kathy wanted a cat,” Dana was eager to point out when the family was asked. “His name was Sport,” Kathy stated, “and he brought us gifts but never birds, only furry things,” She insisted.

Beyond the typical domestic pets the bird sanctuary was known at the time as an ideal place to rehabilitate local injured wild animals and not just birds. Some of these were kept in cages for obvious reasons such as the badger and the bear. Others were manageable as pseudo pets and felt comfortable as part of the family. Joan remembers rehabilitating a particular black squirrel. Long after his release date he banged his tail on the screen door to beg for food.

Kathy took care of a kestrel that had an injured wing. The bird would chase the boys down the hall when David was just a preschooler and put its claws in their hair. David remembers throwing seed down the hallway trying to distract the incorrigible bird, not knowing at his young age that kestrels don’t eat seed.

Laurie took care of two well-behaved ringneck doves she named Pete and Madelin.

Domestic and wild mingled at the sanctuary and the animals knew that it was a safe place… for the most part. Kathy once managed to sled ride into a deer and damage its leg. They fixed him up too.

Once they cared for an injured hummingbird that lived in an open shoe box on the kitchen table. Each day, Dad came into the house for his lunch. One particular day when he left again for work he neglected to close off the kitchen, inadvertently leaving one of the pocket doors open. Sport, the cat, took advantage of this opportunity and had himself a hummingbird lunch. This was Sport’s only misstep as the Sanctuary’s resident cat.

The first rescue animal that Joan took care of was a fawn. She fed it milk from a large beer bottle fitted with a rubber nipple typically used for lambs. She called him Bucky. Bucky survived and became the first inhabitant of the deer pen.

“The presence of such unfortunate creatures became an accepted part of our lives” Joan explained, “but unfailingly caught visitors by surprise.” The first time Joan brought her husband home to meet the family he slept in the rec room that had a door leading to the outside. Investigating a 3 AM scratch at the door, he was greeted by a raccoon who self-assuredly waddled past him and into the house. A comic chase ensued. Six siblings, Mother, and two guests pursued the (semi-tame) intruder to capture him and return him to his cage. Dad slept through the entire ruckus (or at least pretended to).

Joan’s parents-in-law experienced a similar incident on their first visit. She recounts, “The family’s German Shepherd’s food bowl was used to prepare milk-soaked bread to feed a recently rescued baby skunk, who had happily climbed into the bowl to guzzle the contents. The dog arrived, saw the spectacle and—irate at the skunk’s using his bowl or perhaps just responding to a primal canine urge— yelped mightily and, practically bowling the human spectators over, lunged at the terrified baby, who very swiftly sought refuge under the dryer in the laundry room, overturning the bowl in its haste and flicking its tail in a vain attempt to spray. Living in the Sanctuary never ceased to offer surprising and extraordinary events.”

Dana, Laurie, David, and Kathy Van Deusen, sharing memories of their childhood home with the history team, May 2012. Photo by John Gorentz

Childhood Chores

Beyond taking care of the unconventional “pets” and rescue animals for rehabilitation the Van Deusen children had other responsibilities to help keep both home and sanctuary clean and running smoothly. Mother had a garden near the research area and the children remember many hours harvesting potatoes and carrots and the mosquitoes made their chore of picking blueberries annoying at best. During good weather, Joan remembers helping to set up and manage the bookstore on the weekends.

One of the joys of visiting the sanctuary is getting to feed the waterfowl. The children remember the cardboard boxes that they stamped and filled with food pellets and corn, “what seemed an endless quantity,” Joan remarked.

Kathy’s least favorite chore was to retrieve the frozen white mice from the cooler to feed the birds of prey but perhaps the most fun was their after hours chore of fishing for pop bottles that visitors littered into the lake. The sanctuary was quiet and the evenings were cool and who’s to complain if an accidental fish or two are caught during their duty?

Security

When private and public mingled so closely, the barriers have to be monitored. The children knew what was right and wrong and anyone outside of the public boundaries would be challenged. The kids would tell an adult to remedy any intrusion of the private areas. David also remembers needing to be inconspicuous when slipping in and out of the private area so not to encourage others who did not know he was a resident.

Laurie also remembers having no issue with interrupting anyone acting inappropriately towards the animals residing at the sanctuary. No matter what age the offender Laurie would scold, “No, No, no! Don’t do that!”

Some offenders were more audacious than others. Once a man was stopped trying to sneak out the front entrance carrying a black swan. Another time Van caught the man stealing gas from the gas tank meant for grounds utility vehicles by filling it with water. When the thief’s engine stalled after helping himself he was caught.

Life at the Sanctuary was indeed an adventure. Whether it’s the bantam rooster attacking Joan’s feet on the way to the school bus stop or having to detour to the bus altogether due to a brush fire, the daily routine was never dull.

Impressions of Dad’s work

Roswell Van Deusen’s (Van’s) passion for education was evident to his children. Joan sees her father as being a “committed ecologist” long before the term was popular. Though an educator his classroom was found amid the spontaneous elements that passioned him. The children remember the seemingly “endless succession of special groups,” that visited the Sanctuary. There were Scouts, Church Groups, The Michigan Nut Growers Association, and School children. Van would pack his specially outfitted truck with benches in the open bed and tour the grounds with these groups to talked about the important programs under his direction.

Once a particularly high-profile visitor came and the children were not permitted out of the house. Joan recalls Governor G. Mennen “Soapy” Williams arriving with an accompanying cohort. They lived at the time in the director’s residence in the middle of the grounds, overlooking the visitors’ area on the Wintergreen beach. Curious to see the governor in person, however, most of the children, as quietly as possible, and realizing the risking of a terrible scolding or worse if discovered, they climbed out onto the excellent vantage point of the porch roof when the group reached the beach area just below the house. They got to see the politicians “in person” and there was never any reprimand.

Kathy recalls her father’s incredible attention to detail and how each of the educational displays were taken to the next level through the collaborative efforts Van made with the artists who designed the presentation. Van’s keen photographic eye and sharp understanding of shadow and light when creating a black and white photo portrait enabled him to share his view of the Sanctuary with everyone who visited. During his service in the military, Van was a navy ship photographer. His theory was to wait for the sun to go down and then use the remaining light of dusk. His darkroom was set up in the basement of the Sanctuary offices and at the time of this writing still intact.

Van started the Science Fair at Kellogg Elementary school and Kathy and David remember working of project with their dad to show. Van expanded the term science beyond the traditional sense to include art and photography. Kathy specifically remember her project that was sparked by her curiosity in how different trees produced different color wood. She went on a walk through Kellogg Forest with Walt Lamine and chose sample prunings of trees, pegged them to a “Lazy susan apparatus” and showed the differences in trees. She proudly remembers the project earned her a blue ribbon.